From 1966 to 1969, the parents of one of the current plaintiffs, and the grandparents of the current defendants, litigated a property dispute concerning access rights over easements between their respective abutting properties in Abington. Fifty years later, the present plaintiffs seek in the current action to obtain essentially the relief their predecessors in title failed to gain in the previous litigation. The defendants, seeking to defeat a claim that they allege is identical to the one defeated nearly fifty years ago by their grandparents, have moved to dismiss four of the six counts of the complaint on grounds that the present complaint is barred by the doctrine of res judicata, as well as on grounds that the claims in some respects fail to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. The defendants' motion for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(c) was argued before me on April 17, 2018. For the reasons stated below, the motion for judgment on the pleadings will be ALLOWED.

FACTS

The defendants' motion for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(c), is treated essentially as a motion to dismiss under Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6), that argues "that the complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted." Jarosz v. Palmer, 436 Mass. 526 , 529 (2002), quoting J.W. Smith & H.B. Zobel, Rules Practice § 12.16 (1974). In deciding a Rule 12(c) motion, all facts pleaded by the nonmoving party must be accepted as true, but the court does not accept legal conclusions cast in the form of factual allegations. Schaer v. Brandeis University, 432 Mass. 474 , 477 (2000). The documents attached to the plaintiffs' complaint are also part of the pleadings and will be accepted as documents to be considered in deciding Rule 12(c) motions. See Mass. R. Civ. P. 10(c) ("A copy of any written instrument which is an exhibit to a pleading is a part thereof for all purposes"). See also Schaer v. Brandeis University, supra, at 477 (In considering motion to dismiss, "items appearing in the record of the case, and exhibits attached to the complaint, also may be taken into account"). Some of the allegations taken as true for the purpose of the present motion are those contained in the record of the prior action upon which the defendants base their defense of res judicata. In considering a motion for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(c), "a judge may take judicial notice of the court's records in a related action." Jarosz v. Palmer, supra, 436 Mass. at 530. The court takes judicial notice of the record in the prior case.

Accepting, for the purposes of the Rule 12(c) motion for judgment on the pleadings, the well-pleaded facts in the complaint, along with the documents referred to in the complaint, and the court's record in the prior action, the following facts appear:

The Properties

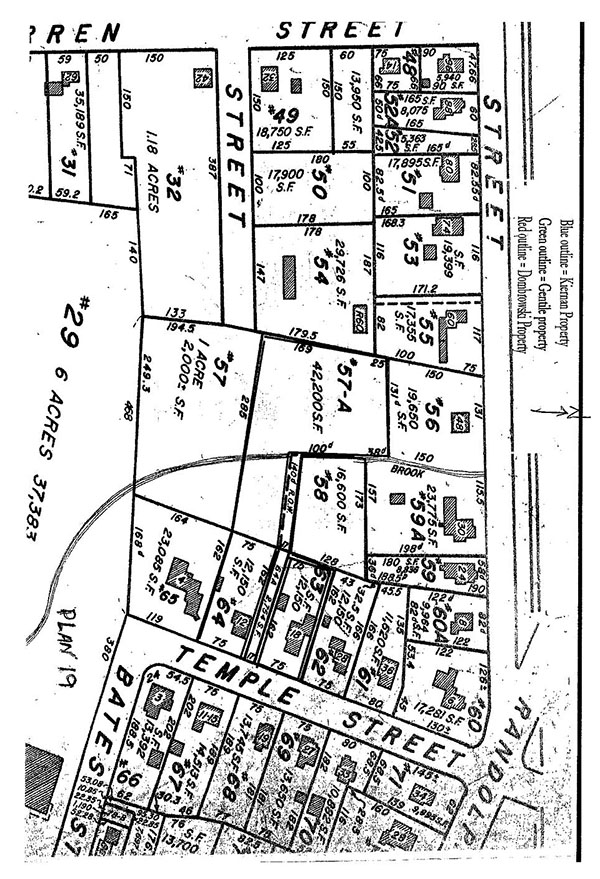

1. The plaintiffs, James M. Dombrowski and Jean B. Dombrowski, husband and wife, own and reside at property at 28 Temple Street in Abington. The plaintiffs' property consists of property now or formerly designated by the Abington Assessor as tax parcels Lot 62, with frontage on Temple Street, and Lot 58, contiguous to and located to the rear, or west, of Lot 62.

2. The defendants James Kiernan, Jr. and Catherine M. Murphy, own property at 12 Temple Street in Abington. The defendants' property consists of two tax parcels, Lot 64, with frontage on Temple Street, and Lot 57A, to the rear, or west, of and contiguous to Lot 64. The defendants' Lot 57A wraps around the plaintiffs' rear lot, Lot 58, abutting Lot 58 to the south and to the west.

3. Assessor's parcel Lot 64A is a strip of land 17 feet wide and 162 feet long, abutting the defendants' land to the south, bounding on Temple Street on the east, and with its westerly boundary coinciding with the rear boundary of the defendants' Lot 64.

4. The plaintiffs claim record title to Lot 64A, and trace their title through a deed to Charles Dombrowski and Adela Dombrowski dated May 13, 1968, and recorded in the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds in Book 3441, Page 339. The May 13, 1968 deed purported to grant, "All our right, title and interest that we may have" in Lot 64A. However, this deed does not include a title reference to the grantors' source of title.

5. Extending to the rear, away from Temple Street, from the westerly end of Lot 64A, is another 17-foot wide strip, referred to as a right of way 17 feet in width and 140 feet in length, extending from the westerly end of Lot 64A, abutting the southerly boundary of the plaintiffs' Lot 58, and terminating at a line coincident with the westerly boundary of Lot 58, where it bounds the rear portion of the defendants' Lot 57A to the west. This 140-foot long right of way is part of the portion of the defendants' Lot 57A abutting the southern boundary of the plaintiffs' Lot 58. [Note 1]

The Prior Litigation

6. On April 26, 1966, Charles Dombrowski and Adela Dombrowski filed a bill in equity against Edward J. Kiernan and Muriel L. Kiernan, concerning disputed rights of access to the rear part of the Dombrowskis' property (Lot 58). [Note 2]

7. The case was referred to a Master, who was appointed by an order dated October 16, 1967. The Master filed his report with the court on November 13, 1967. There was no activity in the case noted on the docket during 1968. On March 17, 1969, the respondents, the Kiernans, moved to confirm the Master's Report. The motion was assented to by the petitioners, the Dombrowskis. The assented-to motion to confirm the Master's Report was allowed on June 12, 1969. A final decree, "assented to and appeal waived," was entered on the same date.

8. The Master's Report, as filed with the court on November 13, 1967, found that the petitioners, the Dombrowskis, were the owners as tenants by the entirety, of the two lots at 28 Temple Street, which I have been referring to above by their Assessor's designations as Lot 62 and Lot 58.

9. The Master's Report found that the respondents, the Kiernans, owned the two parcels comprising 12 Temple Street, which I have been referring to above as Lot 64 and Lot 57A.

10. As for the 17-foot by 162-foot right of way running from Temple Street on the east, westerly for 162 feet, which I have referred to above as Lot 64A, the Master found that he had insufficient evidence to make a finding as to who is the owner of Lot 64A, or with respect to who may have "the benefit" of this right of way. However, the Master found that the petitioners, the Dombrowskis, did not have rights over this parcel. Specifically, the Master found, "I do not find that the Petitioners by express grant or by any other means have any right in or over the 'right of way' from Temple Street which runs westerly for 162 feet."

11. The Master also made findings with respect to the 17-foot by 140-foot right of way running westerly for 140 feet from the westerly boundary of Lot 64A, abutting the southerly boundary of the Dombrowskis' property (Lot 58). Specifically, after finding that the respondents, the Kiernans, owned the 17-foot by 140-foot right of way extending westerly from the 162-foot right of way (Lot 64A), the Master found as follows:

"I do not find in any of the documentary evidence offered in this case that the Petitioners [the Dombrowskis] or any of their predecessors in title were ever granted the right to use either of the "rights of way" referred to in any of the conveyances which were offered in evidence, and I find that any mention of either "right of way", in any conveyance through which the Petitioners claim title to their premises was made for the purpose of describing the land and providing a reference for boundaries. . . . I find it a fact that the Petitioners do not have any right of way on, over or across any of the land belonging to the Respondents."

12. The court's June 12, 1969 Final Decree confirmed the Master's Report, finding in part as follows:

"1. The petitioners Charles J Dombrowski and Adela Dombrowski . . . do not have any right of way on, over, or across any of the parcels of land belonging to the respondents Edward J. Kiernan and Muriel L. Kiernan . . . .

"2. The petitioners . . . Charles J Dombrowski and Adela Dombrowski do not have any right of way on, over, or across a seventeen (17) foot right of way which lies adjacent to the parcel of land belonging to the respondents Edward J. Kiernan and Muriel L. Kiernan . . . which right of way runs westerly from Temple Street for a distance of 162 feet and which right of way is situated northerly of the said respondents' land."

DISCUSSION

The counts in the plaintiffs' complaint that the defendants seek to dismiss make claims, as follows: Count II, to try title with respect to rights in Lot 64A, with the plaintiffs claiming that they have record title in Lot 64A superior to that of the defendants; Count III, to establish an implied easement over the 140-foot right of way on the defendants' Lot 57A, adjacent to the Lot 58 portion of the plaintiffs' land; Count V, seeking a declaratory judgment that the plaintiffs have superior title to that of the defendants over Lot 64A; and Count VI, claiming a prescriptive easement over Lot 64A and the 140-foot right of way. The defendants assert that these claims are barred by the doctrine of res judicata, and that Counts V and VI fail to state a claim for additional reasons as well.

CLAIM PRECLUSION

"Res judicata is the generic term for various doctrines by which a judgment in one action has a binding effect in another." Heacock v. Heacock, 402 Mass. 21 , 23 n.2 (1988). The doctrines of "issue preclusion" and "claim preclusion" are encompassed within the term "res judicata." Kobrin v. Board of Registration in Med., 444 Mass. 837 , 843 (2005). The defendants contend that the plaintiffs are barred from relitigating any claims based on their claims of rights of access over or ownership of either Lot 64A or the 140-foot right of way. The defendants characterize their defense as one based on the sub-doctrine of claim preclusion, as the defendants argue that the claims of superior title and rights of access are the same claims as those at stake in the earlier litigation.

"Three elements are essential for invocation of claim preclusion: (1) the identity or privity of the parties to the present and prior actions, (2) identity of the cause of action, and (3) prior final judgment on the merits." DaLuz v. Dep't of Correction, 434 Mass. 40 , 45 (2001); Franklin v. North Weymouth Coop. Bank, 283 Mass. 275 , 280 (1933). The party asserting res judicata bears the burden of establishing all the elements. Longval v. Comm'r of Correction, 448 Mass. 412 , 416-417 (2007). However, the present cause of action "need not be a clone of the earlier cause of action" to invoke claim preclusion. Mancuso v. Kinchla, 60 Mass. 558 , 571 (2004); Massachusetts Sch. of Law at Andover, Inc. v. American Bar Ass'n, 142 F.3d 26, 38 (1st Cir. 1998).

To the extent one might argue that the present question is more properly characterized as one of issue preclusion, the analysis is essentially the same. "Before precluding the party from relitigating an issue, 'a court must determine that (1) there was a final judgment on the merits in the prior adjudication; (2) the party against whom preclusion is asserted was a party (or in privity with a party) to the prior adjudication; and (3) the issue in the prior adjudication was identical to the issue in the current adjudication.'" Petrillo v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Cohasset, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 453 , 457458 (2006), quoting Tuper v. North Adams Ambulance Serv., Inc., 428 Mass. 132 , 134 (1998).

Identity or Privity of the Parties. Aside from the familial connection between the present plaintiffs and defendants with the litigants in the prior litigation, the present plaintiffs are the successors in title to the property owned by the petitioners in the earlier dispute, and the present defendants are the successors in interest to the property owned by the respondents in the earlier dispute. As the respective successors in interest to the parties who were the owners of the same property involved in the earlier litigation, the present parties are in privity with the petitioners and the respondents in the earlier litigation for the purposes of determining whether the earlier litigation has a preclusive effect on the present action. See O'Donoghue v. Commonwealth, 93 Mass. App. Ct. 156 (2018) (judgment in title claim dating to 1830 binding on present-day successors in interest). "[J]udgment that determines interest in real property '[h]as preclusive effects upon a person who succeeds to the interest of a party to the same extent as upon the party himself.'" Id. at slip opinion p. 4, quoting Restatement (Second) of Judgments, § 43(1) (b) (1982).

Identity of the Claims. Ownership of the plaintiffs' and the defendants' present parcels was expressly made the subject of findings in the Master's Report, and the Master's Report also included a finding that the ownership of Lot 64A, the 17-foot by 162-foot strip, could not be attributed to either of the parties. The Master's Report also included express findings that the Dombrowskis, parents of one of the present plaintiffs, had no right to use, by easement or otherwise, either of the rights of way at issue in the present litigation. These claims decided in the earlier litigation thus are functionally identical to the claims in the present action, in which the plaintiffs claim superior title to Lot 64A (Counts II and V), and an implied easement and prescriptive rights over the 17-foot by 140-foot right of way on the Kiernans' property, as well as prescriptive rights over Lot 64A (Counts III and VI). [Note 3] Although there is no way to determine whether a claim based on the 1968 deed to the Dombrowskis of some interest in Lot 64A was actually raised in the prior litigation, it would have behooved the Dombrowskis to bring the deed to the Master's or the court's attention, as the deed was recorded in 1968, a year before the litigation was concluded. If they failed to bring the deed to the court's attention at that time, the present claim based on that deed is no less precluded. "The doctrine of res judicata precludes relitigating not only the issues raised in the prior action, but the issues that could have been raised." Brennan v. Harmon Law Offices, P.C., 81 Mass. App. Ct. 1125 (2012), citing Anderson v. Phoenix Inv. Counsel of Boston, Inc., 387 Mass. 444 , 449 (1982); Baby Furniture Warehouse Store, Inc. v. Muebles D&F Ltée, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 27 , 35 (2009). The claims being identical, the second element necessary to establish claim preclusion is met.

Prior Final Judgment on the Merits. There is no question that the prior litigation resulted in a final judgment on the merits. Based on the Master's Report, the court entered a Final Decree upholding the findings that the Dombrowkis had no rights of ownership or to use either of the rights of way at issue, and noted on the docket that it was assented to and that the parties had waived any appeal. Accordingly, the final element of a defense of claim preclusion, or issue preclusion, has been established.

The plaintiffs also argue that they should not be bound by the 1969 Final Decree because of extreme medical difficulties being experienced by the plaintiffs' family at that time, continuing into the 1970s, that, according to the plaintiff James Dombrowski, required his parents to abandon the case, and to forego any appeal of the Final Decree. Accepting the factual allegations in Mr. Dombrowski's affidavit as true, the court must take into account that the Dombrowskis were the petitioners in the earlier case, and chose to assert their claims notwithstanding the medical difficulties afflicting their family. There is no indication in the record that the decision to assent to a final judgment that was not entered into without prejudice, and to waive any appeal, was anything other than freely considered and voluntary. Moreover, there is no assertion that the medical difficulties persisted for so extraordinary a length of time as to justify allowing the relitigation of claims that were decided with a final judgment nearly fifty years before the present complaint was filed.

THE TRY TITLE CLAIM

Even without a finding that the counts alleging superior title to Lot 64A are precluded because of the prior litigation, Counts II and V, seeking to establish superior title to Lot 64A via a try title claim pursuant to G. L. c. 240, §§ 1-5, and a declaratory judgment claim, fail to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

The court does not have subject matter jurisdiction over a try title action unless the plaintiff establishes that he is a "person in possession" of the disputed property, and that he has "record title" to the property. Abate v. Fremont Inv. & Loan, 470 Mass. 821 , 830 (2015). The plaintiffs in the present action do not allege anywhere in the complaint that they are "in possession" of Lot 64A; in fact, in paragraph 54, the extent of their alleged exercise of dominion over Lot 64A appears to be that they call the police and send cease and desist notices when the defendants park vehicles on it. They do not specifically allege that they or their predecessors in title have even used Lot 64A for passage after 1965, let alone taken possession of it.

Further, the plaintiffs do not allege sufficient "record title" to Lot 64A. Their title is based on a deed to the present plaintiff James Dombrowski's parents in 1968, which, as is noted above, does not provide any indication of the source of title. The recording of a single deed, which does not provide any satisfactory indication of the source of title granted in the deed, is insufficient to establish the record title necessary to maintain a try title action. Bevilacqua v. Rodriquez, 460 Mass. 762 , 771 (2011) ("The effectiveness of the quitclaim deed to [the plaintiff] thus turns, in part, on the validity of his grantor's title. Accordingly, a single deed considered without reference to its chain of title is insufficient to show 'record title' as required by G. L. c. 240, § 1"). The present plaintiffs' 1990 deed, based on the 1968 deed, which in turn shows no chain of title, fails to establish record title to Lot 64A sufficient to form a basis for jurisdiction under G. L. c. 240, §§ 1-5, or to form the basis of an actual controversy for purposes of stating a claim under G. L. c. 231, § 1.

THE PRESCRIPTIVE EASEMENT CLAIM

Count VI purports to state a claim for establishment of prescriptive rights over Lot 64A and the 17-foot by 140-foot right of way westerly of Lot 64A. Other than the allegations that the plaintiffs' predecessors in title used the two rights of way regularly between 1951 and 1965, [Note 4] there are no specific allegations of adverse or prescriptive use of these two parcels at any time after the resolution of the prior litigation. In addition, since the Kiernans do not claim record ownership of Lot 64A, and the prior litigation determined that neither of the present parties has any claim to record ownership of Lot 64A, prescriptive rights with respect to Lot 64A would have to be established against the true record owners of Lot 64A, and, whoever they are, they are not parties to this action.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the defendants' motion for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(c), is ALLOWED. Accordingly, it is ORDERED that Counts II, III, V and VI of the Verified Complaint are DISMISSED.

So Ordered.

JAMES M. DOMBROWSKI and JEAN B. DOMBROWSKI v. JAMES KIERNAN and CATHERINE M. MURPHY.

JAMES M. DOMBROWSKI and JEAN B. DOMBROWSKI v. JAMES KIERNAN and CATHERINE M. MURPHY.